Production Reference

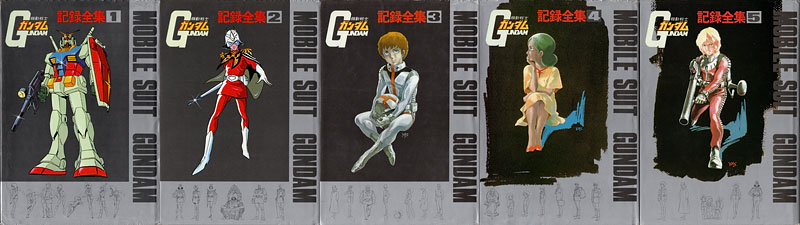

Mobile Suit Gundam Complete Works was a five-volume series covering the original Mobile Suit Gundam, published by Nippon Sunrise between December 1979 and October 1980. Each volume contained illustrated episode summaries, setting art, and exclusive essays and interviews.

In addition to the Gundam Setting Notes reprinted in the first volume, and the Gundam Third Cours Story published in the last one, I've translated a selection of staff and creator interviews here.

The following text is copyright © Nippon Sunrise.

Throughout the planning and production of many previous robot anime works, I was dissatisfied by their lack of novelty, and the sense that something was missing. So I wondered whether we could create a completely new kind of SF action that had never been seen before, and include robots in it. That was the initial impetus that led to Mobile Suit Gundam.

One day, I received some helpful advice. "The biggest shortcoming of robot anime is that they seem to have SF elements, but they actually have virtually none. The planners don't know much about SF, and they don't understand it. There's an SF book called Starship Troopers that features robotic mecha, so you should try reading it sometime..."

Coming across this one SF novel was the thing that decided the creation of Mobile Suit Gundam. With the image now fixed, the concrete planning work progressed steadily.

Together with the main staff and the brains in the planning office, I proceeded with the plan and series setting, and finally Mobile Suit Gundam was born. Naturally, you can't make a program with a plan alone. It's created through the collective effort of all the staff involved in the production. Please don't forget the hard work of the many people who participated in the production behind the scenes.

It's improper for someone involved in the production to comment on their own works outside the film itself. The idea that we should nonetheless document the beginnings of Gundam in this kind of format is obsessively fannish, and I don't care for it. By its nature, film is something meant for the general public.

However, supposing you're an obsessive fan, I suppose I'd be happy if you were to take away from this the ideas about structure and detail that led to the Newtype narrative emerging from the world described here. In animation, how can we create realism as a preliminary step to plunging into fantasy? That experiment was the main theme in the production of Gundam.

It's amusing to think how I might feel about this work if I live for another hundred years, and then watch it again. I doubt that people a hundred years from now will have the same sensibilities and ways of thinking. But I think at least the way we live as human beings won't change, and I hope that it doesn't.

It's not such a big thing, but it's fun to imagine watching this work again a hundred years from now, and seeing how big a role it's played in my personal growth.

I'm so tired! Somebody please help me...!!

I enjoyed watching Gundam, thinking what an amazing work it was. But when I suddenly found myself directing for it, I started out with some trepidation. I made a lot of blunders due to my inexperience, and I was constantly in a cold sweat... So first of all, let me apologize to Mr. Tomino!

But I've really enjoyed getting to work on Gundam, which depicted the mecha in such a mechanical way, and above all I've learned a lot from it. Though I was only in charge of four episodes, I'm delighted by my good luck.

Most protagonists in TV anime have extroverted personalities. It's easier to depict such people, and you could even say it's more proper. But nonetheless, at least once, I wanted to try creating a work whose protagonist had an introverted personality. And now I've done that with Amuro. Mr. Tomino was of the same mind about the setting for the protagonist, and we were fairly successful.

Another one I'm attached to is Shiden. With his pragmatism and cunning, Shiden may have been a key character in helping Amuro stand out as a person...

When I started working on Gundam, I had a feeling, albeit a very abstract one, that I might be able to achieve something. I have that impression with every work, but I felt it especially strongly with Gundam. And I think to some degree I've been able to accomplish that.

Of course, in a sense I was able to write quite freely. I think that was largely due to the efforts of the staff, who could take a work with such hard aspects and bring it to life in visual form.

The production site started out with many constraints and a shortage of staff, but the days were so busy we had no time to be discouraged. During these days that resembled the White Base's own logbook, the determination to create a long-running series and the agony of an overwhelming amount of work were dizzyingly intertwined.

As the end of the whole process comes into view, I'm starting to feel I can see a glimmer of light. This is the last work I've been able to participate in during the 1970s, and it's one to which I'm emotionally attached.

It was after the episode 34 rush film. "What's with this piggy Mirai...?" Yikes! Th-that Miss Mirai I'd drawn...

When Mr. Yasuhiko was animation director, I used to look forward to the rushes! Now, every time I watch them, I lose my appetite. Waah, I'm so sorry the characters don't look like themselves!

Through the efforts of Mr. Tomino and the scriptwriters and episode directors, each of the characters was given their own individual flavor, and Mr. Yasuhiko accompanied that with his distinctive characterization and realistic performance... Then various other things happened, and just when the story was about to reach its climax, Mr. Yasuhiko was hospitalized. What a pity.

After that, Mr. Tomino and the others ended up doing some drawing as well. As an animator, seeing that made my face twitch... Well, I guess people can adapt to sudden changes in their environment. Do I have to push myself too...?

I was amazed by the preview screening of the first episode. Then I started grappling with Mr. Yasuhiko's uniquely quirky characters, and before I knew it, a whole year had passed. But I think no other work has taught me so much.

Gundam is a work even more serious than Zambot. The content is more sophisticated, and this long-running series has a worthwhile story that everyone loves, but... The production situation is no better than it was then. Instead, since there are more episodes, in production terms it's as difficult as ever.

My stomach ache is gradually intensifying, and I worry I'm going to collapse like Mr. Yasuhiko! That, too, was a huge shock. To all the viewers, as well as enjoying it, please also remember how hard the staff are working to make it!

Gundam is amazing! There's so much of it! There are so many different characters, mecha, and locations that I don't know what's what. Even making the copies is exhausting. It's so complex that we can never get the animation finished. There's no schedule! There are no animators! There are no finishers! There's no background art! So I'm always up all night. I don't have time to write comments! I hope this is over soon...

It must be nice for the people watching it. I think it's really good. But I'd rather be watching it than producing it.

Ga! Patience, patience. The outside contractors are complaining. N, huh! That episode was so tough that I'm speechless. Da! It's no good, the animation isn't done. Mu! This schedule is hopeless! (1)

When you ask me for my memories, this kind of thing is all that comes to mind. Gundam may be fun to to watch, but it's really exhausting to make. This was the hardest work I've ever been responsible for, Mr. Tomino. Hurrah for XX!

I'm a production secretary in name only. I've spent most of my time managing the bank. (2) There was so much bank material I often thought about quitting...

It's only because of the gentle voice of the chief director that I've been able to make it through. By the time this story comes to an end, perhaps I too will have grown into a tough woman like the ones who appeared in Gundam.

I only joined halfway through, so I'm not sure what to write. If I had to choose, I'd just say that I think it's been really difficult. The hell of searching for cut bags is a task that can't be described in words. I had no idea why I couldn't find the backgrounds or the cuts, so all I could do was laugh it off. Oh, I'm so tired. I'll never forget somehow cutting a background in half. That was awful. Okay, I'm done.

(1) Kusakari is spelling out "Gundam" with the first syllables of each sentence, but that doesn't really work in translation.

(2) In anime, a "bank" is an archive of old cels which can be reused later as stock footage.

"What do you think about Gundam?" These days, people ask me that a lot.

"About Gundam?"

"That's right."

"Um, well..."

For a moment, I'm not sure how to reply. Then they hit me with a rapid succession of questions. "What do you think about Newtypes?"

"Um... There's a question."

Once again, I'm at a loss for words. I feel like a bad student interviewing for a job. As I keep on saying "Um..." they start to look puzzled.

"But you wrote the scripts, didn't you?" They glare at me with a suspicious expression.

At that point, I go on the offensive. "Whatever you understood when you watched it, whatever you felt, that's Gundam." Blurting out this non-answer, I go back to slurping the coffee that's now gone cold.

It's tough, because I understand their desire to ask. Any fan, to a greater or lesser extent, would want to ask the staff directly about what you perceived with with your own eyes and ears in order to "confirm" it. I've experienced that myself when I was crazy about a movie.

So why in the world can't I give a ready answer when it comes to works I was involved in? Why do I feel so weary when I'm talking about Gundam? It's simply exhausting. That's honestly my state of mind when I've finished making a work.

This weariness comes from the fact that what ended up on film was very different from what was okayed in the script stage. In other words, it's tiring because of the twofold gap between my dissatisfaction that my script was treated as nothing more than a rough draft, and the fact that when they mention the title of the script, I'm expected to answer questions about the filmed version.

If I hate it so much when they tinker with my scripts, shouldn't I uphold my independence by leaving the staff? I completely agree. But I didn't quit... Never mind, I'm just frustrated with myself.

Even though they tinkered with my scripts, the results won the hearts of countless fans. It became popular. In that case, it just means the director and the rest of the staff were really great, and as a single writer I should quit grumbling. It's better that I meekly accept my defeat.

This book is meant to provide "confirmation," so to speak, for those who came across the work called Gundam at some point in their adolescence and became fans. In such a book, why I did I begin by writing about my personal feelings, which don't matter to the reader?

It should go without saying, but I know that whatever I say, however laughable, won't have any impact on the world of Mobile Suit Gundam. And if I talked about Gundam without taking that into account, then I'd be lying to you. That's what I thought. So what was the point of my writing something, and them devoting pages to it? Then I understood.

This book isn't a so-called trade publication. Maybe the creators aren't all going to come together and shout "Hurrah for Gundam!" The fans have already seen articles like that in so many other places...

Since I began scriptwriting, Gundam was the first work on which I've been able to write the first episode of the series. This was also the first time at Sunrise where I was involved from the planning stages. In that sense, Gundam is a landmark work for me.

It was in the heat of summer. The planning chief, Mr. Yamaura, told me he wanted to do a show about a team who use robots. Honestly, I thought "What, another robot show?" But if I was going to do it, I wanted to do something different from before. No matter what, I had a strong desire to create at least one world that would break down the simplistic formula that anime meant programs for children.

Then I heard that Mr. Tomino was going to direct it. He was a senior I'd known for a long time, but the first time I'd ever worked with him as a scriptwriter was on Zambot 3. I then worked on Daitarn 3 as well.

Mr. Tomino's goals for the anime aligned with mine in many respects. Though it was his original work, he let me do as I pleased and, above all, write whatever I liked. I also had a concrete understanding of his objectives and preferences. If I was working with him, then maybe this time we could make something new... I thought Mr. Tomino could definitely do it (and he actually did). So I took it on with considerable enthusiasm.

We held a series of planning meetings in the Sunrise planning office, and with the help of Mr. Iizuka, we wrote up a proposal to submit to the TV station. In the meantime, the original story creator Mr. Tomino was also establishing and fleshing out a solid worldview, Mr. Yasuhiko was creating the characters, and the rough contours of Gundam were taking shape.

This is a little out of sequence, but when we we began discussing the plan, I suddenly thought of Battles Without Honor and Humanity (screenplay by Kazuo Kasahara, directed by Kinji Fukusaku) and I secretly wanted to create that kind of youth ensemble drama in anime. Young people are thrown into a certain time and situation, they get hurt, some of them find joy in life, others suffer setbacks as they attempt to climb to power... Rather than highlighting a single person, I wanted to depict the intertwined images of many young people. My own vision began to grow.

In hindsight, I wish I'd discussed this more with Mr. Tomino at the time. Mr. Tomino had no objection to the idea of a youth ensemble drama, but he was thinking of it as fairly structured hard SF, leading to the appearance of the Newtypes that caused so much trouble later on. That's the reason the two of us ended up clashing after production began.

Even though it reduced strife, you could say there was a dramaturgical conflict between my style, which emphasized human inconstancy and activity, and Mr. Tomino's attempts to venture into the conceptual realm with things like Newtype theory. I didn't have a problem with depicting concepts, but I was rather concerned about how we conveyed them to the viewers (and not necessarily just with words).

Even if it's in an indirect way, communicating with others is the most important thing for a writer. However lofty your theories, if you can't convey them through film, then I think the presentation of your theme is a failure. My one criticism of Gundam is that it was so crude in trying to communicate with others. That's all.

"Not understanding it is part of the fun." I completely understand that, but it's not how scriptwriting works. Maybe that's just my own opinion, but...

Let's get back to the story. After we submitted the proposal to the TV station, we didn't hear back for a while. Then, as winter began, they gave us the go sign to create the work.

No matter what, I had to get the long-distance race off to a good start as the first runner. The rest of the staff were waiting with empty hands. It was a hard struggle, and the first episode was finished considerably behind schedule.

When I started on the script, my first thought was that I should avoid advancing the story too much in the first episode, and that this was a good place to give the viewer (I can say now that I was thinking of the target audience as middle schoolers and older) a straightforward depiction of daily rhythms and a sense of everyday life. Rather than the story driving the people, I wanted the people to create the story.

In the first episode, I wrote a scene where Fraw Bow comes to tell Amuro about the evacuation order. This is where we first show the viewer the relationship between Amuro and Fraw Bow, and their respective personalities.

In this scene (though the nuances changed a little in the film) the helpful Fraw Bow rushes into Amuro's room and finds him engrossed in building a microcomputer. Bustling around, she asks about his towels and underwear, at which point Amuro gets annoyed and replies that he can do his own laundry. (1)

Why is Amuro annoyed? Perhaps any boy who's reached middle school will recognize this, but I wanted to show that Amuro, too, is familiar with "male biological functions." I don't want you to think I'm being dirty. And I'm not bringing up that scene to complain that it didn't make it on film. What was completely different from the anime scripts I'd written up until now was that I emphasized trivial details like that because I wanted to depict flesh-and-blood humans. That's what I wanted to say.

Not just I, but the other writers as well, focused on this point. I think Mr. Tomino's direction expressed that with considerable, no, with even greater skill.

Soon after I finished writing the first episode, I saw a preview of the completed version. I was honestly shocked. The sharpness of the direction, the expressiveness of the performances when Amuro and Fraw Bow are caught up in the fighting, and the sense of perspective in outer space were all truly superb. Even allowing for my annoyance at Char's abrupt line, it was amazingly well executed. (2) The staff, who had previously made nothing but minor works, were fired up with enthusiasm for people to watch it.

Even in the first episode, I had a premonition that my world was going to be violated. I still remember burning with a strange fire, determined to stick with it to the very end, even if I had to fight with the director.

Just to be clear, I fought constantly with the director, and we had a lot of pointless arguments and said scary things. But that doesn't mean we couldn't work together. If anything, I was afraid we'd get too comfortable with each other. Even though we clashed, that's just part of the job, and it's entirely natural. That's why I've done three works with him (though this one pretty much wore me out).

For the sake of Mr. Tomino's fans, I should add that although he's scary on the job, outside work he's a kind and gentle person.

Now let's talk about the characters. "Which of the characters is your favorite?"

Somehow, I'm never at a loss for words when it comes to talking about people. "Shiden and Amuro."

From what I hear, Shiden is actually quite popular. But when the broadcast began, people would give me strange looks if I replied "Shiden," never mind "Amuro." But I'd say those were the characters I was most interested in.

This might sound like an excuse, but the reason I didn't leave the staff despite everything that happened, aside from the fact that my livelihood obviously depended on it, was that I wanted to see those two through to the very end. Perhaps that's just because of Mr. Yasuhiko's characters, though...

Otherwise, for some reason I was attracted to Matilda, Miharu, and Sleggar, even though they were more like guest characters than main ones. As for the enemies, I liked Garma's troubled persona.

The fans might stone me for this, but I wasn't that fond of Char. If we'd been able to express more of the ambition, lust for power, and other human desires hidden beneath that quiet exterior, I'm sure I would have liked him more and taken an interest in him.

While I didn't think much of Bright at first, as we neared the final episode, I somehow became fonder of him as a character. He really expressed the loneliness of the leader's role. But it was already too late.

Looking at it like that, characters are truly strange things. They can live on despite their creators.

It seems like I've just been scribbling down complaints, but now I only have a few pages left. So I'll try writing a little about my favorite of the ones I wrote, "Reunion With Mother."

In hindsight, for some reason the ones I wrote tend to focus on close-quarters fighting, in other words defeating enemies while seeing them at close range.

I'm not sure when, but I once read a memoir by a young American who fought as an ordinary soldier in the Vietnam War. The main mission of this young infantryman was to roam around the countryside exterminating guerillas. When the war eventually ended, this young man returned to his homeland, but he'd lost the will to live.

Then he heard another young man who'd joined the air force bragging nonchalantly, without a care in the world, about how many enemies he'd killed in the war. He reflexively replied, "It's okay for you. When you kill people with missiles from the air, you don't have to see any human beings, but I've killed people who were right in front of me. You understand me? Human beings who were still breathing until just before we met!"

Comparing these two young men, I realized the one who couldn't help screaming that had been "hurt" on the battlefield. To the other one, it had just been a game. In thinking about war, it's really interesting to compare these two. You could say this episode was a reflection of my shock when I read that.

When Amuro killed someone right in front of him, he must have been changed. When he experienced this, he had a moment of hurt and confusion. But might this also have been a rite of passage in becoming a warrior, to numb his senses to the idea of killing people...? (3)

I believe human life is precious. Nonetheless, in a war, even I could become a killing machine. What happens at the turning point where you either pull the trigger, or don't? I think Gundam is also a work that makes you consider that.

In this work, Mr. Tomino tried to depict the world of the "Newtype" concept. But I think the Newtype theory is hard to describe, and it was a bit of a stretch attempting to fit a brief explanation into such a limited number of episodes. That may be a harsh way of putting it, but I think it was unkind to leave it feeling only partially resolved.

My own idea of Newtypes is different from Mr. Tomino's, and it's a much simpler one. For instance, if we describe someone vertically oriented, or a pyramidal society, as being intrinsically "Oldtype," then someone who extends it horizontally to everyone else would be a kind of hippie, and a Newtype is someone with that sensibility. I thought of it very simply.

Since Mr. Tomino had gone to the trouble of presenting such great "raw material" that anticipated and implied a future society, I was a little disappointed, and I felt that my own abilities were insufficient to live up to it. In my view, you should first show people who aren't Newtypes as an established fact, and then keep on showing them as a comparison.

For example, when Char says "I'm not a Newtype," then you have to ask what a Newtype is. When Char joined the Zeon forces, at first he was aiming for revenge, but I think he also wondered whether he himself could reach the summit of power. In this moment, Char is perplexed by the realization that part of him is still oriented to the older type of power structure. I think it would have been interesting to make that confusion more clear.

When it comes to revenge, I think even in that future society, humans still can't escape matters of the blood. They kill their fathers and brothers, and in the end, the older types can live only in humanity's most primordial sludge. But I think there will also be some people who are narrowly focused on who's high and who's low, and some people who no longer care about such things.

I believe Char is someone who straddles both these positions, and understands them both. So when a Newtype like Amuro appears, that becomes a cautionary example for him, and even though he really wants to rise to a position of power, he feels somehow uncomfortable about it. Thus Char is frustrated because he can't commit to either, while Amuro is becoming a killing machine whether he wants to or not. In other words, friend and foe are both wounded young men... I wanted to throw that in at the end.

I think Amuro can no longer be anything but a warrior. In the end, he can't go back to normal society. Perhaps only Fraw Bow and Hayato will be able to return to everyday life. I think when the war ends, those two will be able to live as a new family.

And I think it's inevitable that Lalah comes from the Third World. Our current political sphere is divided into West and East, but I think places like India, Burma, and the Near and Middle East will have a tremendous influence in the years ahead. I'm sure those areas will have a big role in the future. As for Lalah, I wanted her to appear in a slightly simpler form... as a symbol of hope for young people facing the future.

It's fine if it's challenging, but I think you have to show it through film, not through words. So to the extent people didn't understand it, I believe it's a mistake to supplement it through things like magazines.

Writing scripts, of course, is a struggle with the director. As a scriptwriter, you always have high expectations for how well the director understands your aims, and then to what extent they're able to translate them into film. And writers are naturally quite attached to their characters and their human relationships. To me, whether it's SF or anything else, the work is ultimately based on human beings. So whenever something is trimmed a little, of course I'm unhappy.

It may have been a success in the end, but from my personal point of view, even if I was just being indulgent, I don't entirely approve. I appreciate that it's well regarded, but inevitably I still wonder whether it was really good enough.

Born in Itabashi, Tokyo on May 13, 1944, and raised in Nerima. Of course, he had a deep connection to animation.

He dropped out out of Chuo University in his fourth year. In other words, in his fourth year, just as he was looking for something interesting to do, he happened to end up going to visit Mushi Pro at the invitation of his friend Mr. Rintaro (director of Galaxy Express 999).

He was stunned when he went to visit. There were people playing shogi and eating meals as they worked. Were there really nice companies like this in the world? He begged them to let him work there, and he ended up joining Mushi Pro. (4)

At the time, Mushi Pro didn't have a literature department, and it seems they asked him to do some drawing as well. Mr. Yasuhiko joined the company just as they started doing a work called Wandering Sun, and Mr. Tomino was there as well. (5) Thus, by this point the three talents who would be the core of Gundam had already met.

His works somehow always end up being "gentle." In order to show this "gentleness," he also shows war and filth. He says that when humans try to conceal the filth, they lose sight of what's beautiful.

Even in the space age, and even if it wasn't comfortable, he'd still want to live on Earth. So he well understands the feelings of Old Man Smith, who goes to a space base carrying coffee beans in his pocket.

(1) This exchange, which happens as Fraw is packing Amuro's bag for the evacuation, was cut from the final animation.

(2) Char's famous closing line in the first episode doesn't appear in Hoshiyama's script. It may have been added by Tomino in the storyboarding stage.

(3) Hoshiyama uses the Japanese phrase fumi-e (踏み絵). Under the Tokugawa shogunate, this was a religious image that suspected Christians were required to step on, to prove they weren't members of the outlawed religion. This can be used metaphorically to describe a forcible test of loyalty.

(4) Hoshiyama joined Mushi Pro in 1967.

(5) The Wandering Sun anime began airing in April 1971.

When I started on this work, I had terrible trouble remembering the characters' names. Honestly, I think it took more than 20 episodes until I could match up the characters and their names in my head. The names of the mecha characters were even harder, and that once led to a ridiculous argument with the chief director. Anyway, all of the staff were pretty much at his mercy.

I can't think of any other case where my own concepts underwent so many repeated changes. At first, I was expecting a worldview like that of Zambot, but the ideas kept getting more and more realistic, so I was pretty bewildered by the time I made the setting.

I'd been planning to give the props and so forth functional and innovative designs, but the chief director's opinion was that everyday items we use today should be incorporated into the Gundam world as is. I think this created a more immersive feeling for the viewer, and brought warmth to the screen. No matter what you pick up, you can only admire the profundity of Mr. Tomino's imagination. On the other hand, there were many occasions where my lack of study was exposed, and I learned something about how art should be done.

First, I'll write about the design of the White Base's interior. I envisioned the control room as a dark space where the shining screens of the computers would stand out. I also made the entire thing dark because I figured the bridge of a warship should be dark during battle conditions. I gave the other passageways and rooms the same uniform dark tone as well, because the backdrop was a state of war.

As for Side 7, whose interior is a cylinder 6 kilometers in diameter, I had a terrible time figuring out how to depict the scene. If you look up at the sky, you should should obviously be able to see the ground surface on the opposite side. After arguing back and forth about how to render this, we ended up putting a cloud layer just like Earth's in the middle, so that the land area overhead is hidden by clouds. The ground surface you're standing on rises up on both sides, vanishing into the clouds. That's how I ended up depicting it.

In the final episode, the interiors of A Baoa Qu (it actually took me a very long time to remember that name) emphasized its cold mechanical nature, but in hindsight I didn't go quite far enough.

After the end of any work, I always have a succession of regrets about my lack of imagination, and I worry that I'm out of my depth. But I have the impression Gundam ultimately ended up as Mr. Tomino intended. I'm certainly looking forward to his next work.

Whether it's a work that focuses on the natural world, or a work like Gundam that focuses on mechanical SF things, I think the job requires a similar amount of ability when it comes to the background art setting.

But when it came to Gundam, I wasn't trying to add anything particularly new. Mr. Tomino himself didn't request anything too drastically advanced, and in general he wanted to keep it realistic. So I think I was able to do the job without feeling too much pressure, using fairly normal thinking.

However, at first I found the work quite hard to understand. I was pretty confused, and honestly I was worried about how it would turn out. Usually, or at least in his previous works, Mr. Tomino tends to make things comical once the story has progressed to a certain extent. But I think with Gundam, he focused on one thing and stuck with it.

The first things I did for Gundam were the White Base interiors, which involved a lot of sickbays and control rooms and so forth. Then I started on the colony. In general there were just these two categories, so it didn't require a vast or infinite number of color expressions. That constraint was very helpful.

When it came to the color schemes, the characters' colors had already been decided, so I tried to be careful to match them. The characters' colors were so vivid that I couldn't viscerally accept them, and I had trouble matching my own color scheme to the color images that other people had done.

As for the bridge of Char's Musai, there were no particular constraints, so I had a lot of freedom in doing it. But it ended up becoming the final draft because they decided it was interesting as it was, and that made it hard for those of us who had to paint it. (1) With things like engines, the more detailed the depiction, the more it brings out the mechanical feeling. If I gave the hangars for the mecha characters the same color scheme, it would be hard to understand the scenery arrangement, so I had to vary the colors for each of them.

Since outer space is an absolute void, we thought it would be most appropriate to make it all pitch black. In general there aren't any bursts of bright, warm color, and we made the colors uniformly cold in order to intensify the story with a dark overall image. I think that ultimately worked out.

I feel we were able to depict an eeriness that could actually exist in the near future, and in that sense, the content was really profound. In this work, even those of us who were responsible for the background art setting were able to throw ourselves into painting with unprecedented freshness.

At first, I had a lot of resistance to borrowing directly from NASA's plan. I thought it would look like we were just copying. But it was Mr. Tomino's wish that we proceed like that, so we put it into action. It was actually quite difficult painting in detail within those parameters, so we had to make adjustments as we worked on it.

Adjusting things to make the work easier was more challenging than doing the actual artwork. After all, in the NASA materials, things like residential buildings were depicted in tremendous detail. For the sake of the schedule, we had to simplify them as much as possible, using an approach that made them easier to depict.

Since the colony was a cylinder 6 kilometers in diameter, we painted in clouds so that the ground surface overhead wouldn't be visible. I'm not sure why, but it seems like clouds form in the middle in NASA's O'Neill plan as well.

And as for the sun, a necessity for the colony, we followed Mr. Tomino's ideas for the setting and just turned them into concrete images. Personally, I don't think about these kinds of mechanisms in a lot of detail, and just depict them according to the director's intentions... That's my job, after all. Thus, where Gundam is concerned, I don't think I came up with any ideas of my own.

But the O'Neill plan is really magnificent. As I proceeded with the job, looking at NASA's samples, I thought this could truly be possible in the near future. And with Gundam, I remember feeling pretty cool as we created it, thinking we might be closer to our ideal when that time comes thousands of years from now. I think it's wonderful that there are people actually planning things like this.

Though I'm personally interested in the O'Neill plan, of course I'd prefer to live somewhere with a genuine blue sky like that of Earth. So I don't think I'd want to live in outer space...

In the unfolding story of Gundam, one of the most important parts of the location art was the space colony setting. This setting was based on NASA's O'Neill plan.

The O'Neill plan was an idea for space colony islands created by Dr. Gerard K. O'Neill, a professor at America's Princeton University, in 1969, the same year that Apollo astronauts first set foot on the lunar surface. In the United States, preparations are under way to realize this within a few decades.

According to this plan, because Earth will be damaged by population growth, industrialization, and the energy crisis which is surely coming in the near future, the people living there will emigrate to space in search of limitless cheap energy, new territory, and resources. Though we call this emigration, they wouldn't be moving to other planets, but to space islands even closer to Earth than the Moon.

The plan is that the interior of the island would provide completely identical living conditions to Earth, including recreational facilities and a comfortable climate suitable for human life. Reflectors are also installed on the colony island, and since the rotational axis of the island itself is always pointed at the sun, they are constantly illuminated by sunlight. The length of the day and night is decided by the inhabitants. It seems the atmosphere is made from lunar oxygen and hydrogen transported from Earth.

This magnificent, dreamlike plan should become possible in the first half of the 21st century.

The job of a background artist is to concretely express the director's image, so the first issue is that of painting. In this job, you have to be able to handle a brush. Painting is relatively easy for those with experience, but a lot of trouble for inexperienced people who can't use a brush.

As an art director, I'd like the work to look exactly as I painted it. But that's not possible for people whose technical improvement is slow, and that's often another source of trouble.

No matter how talented someone is, they still need to accumulate enough experience to depict images that will be approved. So to be perfectly honest, you should be prepared to spend ten years on that.

Born on April 7, 1944. Since he was young, he loved "moving toys" above all else.

He was born and raised in Ueno, Tokyo's back door. There was a department store conveniently close by, so he always went to the toy department to play. He went there day after day, playing with toy buses and trains, which may have been his motivation for becoming a mechanical designer.

After graduating from Okachimachi Middle School, he joined Toei Doga and studied coloring and inspection. Since he was young, he did many different part-time jobs, and so he well understands the hardships of people working in various sections. Even now, when he remembers those days, he's careful not to burden others in his own works.

After this, he went on to Tatsunoko Pro, and then established the background art and design company "Mecaman" in 1976.

It's been 20 years since he began working in anime, handling mechanical design as well as background art setting. Mr Nakamura's sensitive powers of description and techniques are the fruits of the effort he's accumulated over many long years. It's surely an inner strength. Though at first glance his expression appears peaceful, his overflowing enthusiasm for anime work is apparent.

When time permits, he enjoys playing guitar, listening to records, and building plastic models. Recently, however, he's been so busy that it's hard to find the time.

Mr. Nakamura's warmth, sincerity, and extraordinary patience, which enable him to approach everything with a positive attitude, are surely the source of his great confidence.

(1) The Japanese verb kaku (描く) encompasses a range of meanings such as "draw," "paint," and "depict." I've generally translated it as "paint" here since this is the final form of anime background art.

At first, I thought we were going to follow the Daitarn route, and we'd be making an old-fashioned robot show for children. I never imagined it would become a work like this. After a while, though, I heard some talk about playing around a little... or rather, trying to do as we pleased for the first cours or two. I had a hunch we might be making something fairly elaborate.

When Daitarn ended, I remember Mr. Tomino was talking about researching various things in detail, and creating some kind of serious work of art. But I don't clearly remember whether that was actually about Gundam.

I'd always wanted to try doing something in earnest, for example by preparing all the materials for clothing, food, and shelter, even if it was just a fantasy about what things might be like in the future.

With things like Daitarn, it took more than half a year for the story to take shape and to go from draft to final version. By comparison, I think this was much easier.

Normally, when I'm designing a three-dimensional mecha, it strongly expresses the sponsors' wishes. But unlike previous shows, the Gundam didn't have any complex transformations or combinations, and there was only the Core Fighter which changed into the torso. So I didn't have to think about how people would play with it when it was merchandised. As a result, I didn't have any trouble at the start of planning. In fact, that may have been the easiest part.

For other works, I'd make wooden models and use them to study the structure and transformation. But that wasn't necessary with the Gundam, and I proceeded with sketches alone. Of course, Mr. Yasuhiko did a lot of work on it later on, and I think that's why it turned out so well.

For the first couple of cours, I was creating things based on discussions with Mr. Tomino. Starting with the second cours, though, my schedule got very busy. Since I now understood what Mr. Tomino was looking for, he started giving me roughs and then I'd simply clean them up. So in the second half, the designs were mostly as Mr. Tomino wanted them, but on the other hand I was a little dissatisfied.

Well, this is just hindsight, but I think I can say it now the work has ended up being fairly successful. For the mecha in the first half, which were left completely up to me, I was drawing them with an awareness of the design differences between the Federation Forces and Zeon forces. But once he started giving me rough drafts, they'd end up just like that. So of course, the design characteristics got all mixed up.

At first, I was intentionally making the Federation Forces mecha rectilinear, while the Zeon forces mecha were curvier. But in the second half, the Federation Forces ones also started having weird, slightly curved designs, and the distinction was lost. Looking back, I think it might have been better if I'd stuck to my own design policy. But of course, it was due to my own negligence that I didn't say anything at the time, so this is all hindsight.

There are some works where I submit final drafts and they're rejected. But I believe mecha aren't created by one person alone. For example, when it comes to the main mecha, you have the sponsors and the intentions of the production side. Everyone contributes their ideas in the process of creation, so I don't have the sense that I've made it with my own powers alone. In other words, we all created the Gundam.

This is particularly true when it comes to animation. In animation, there are various sections such as key art and in-betweening. As they discuss it together, the people from each section combine their efforts to create a good work.

At the start of planning, the sponsor requested three mecha, which were the Gundam, Guntank, and Guncannon. There was nothing about Zeon mobile suits. (1) But personally, the mobile suit I'm most fond of is the Zaku.

At first glance, the Zaku looks very flexible, but you only get that impression because it happens to be represented with curves. From the beginning, I was thinking of it purely as an armed vehicle. Of course, since it's a mobile suit rather than a traditional robot, my underlying intention was to depict it in a more science-fictional way.

As for the Zaku's performance, I'll leave that to the experts because it's a different field. But when it came to the evolution of its form, I felt it was important to give the impression it was changing in order to develop as a weapon, with the original Zaku as the basis. So I deliberately avoided turning it into a completely different form, and retained all of the initial image.

Of course, it had different colors from Char's Zaku for the sake of characterization. It was Mr. Tomino's idea that Char's Zaku should have a single eye and a horn.

Fans often say the legs of the Gundam and Zaku resemble those of the Stormtroopers in Star Wars, but unfortunately I've never seen Star Wars. I never watch SF movies or anything of that type. The reason I drew the designs that way, in the case of the Gundam, was because I was incorporating human anatomy. My thinking was that I could give it a more humanoid silhouette if I distorted the muscles and turned them into something mechanical.

I'd actually created a character close to this during Daitarn. We didn't use it in Daitarn, and it was just lying around in the planning office. When Mr. Tomino discovered it, he decided we should revise it and put it to use.

It was a spaceship that separated into three parts, each of which transformed into an independent vehicle. In those days, when it came to spaceships you'd naturally think of the ones that appeared in Yamato, so Mr. Tomino thought it might be nice to have a spaceship like this instead. He pulled it out, and I guess it ultimately led Gundam to success.

The other ships such as the Musai, Papua, and Zanzibar were also created with a certain degree of intention that they shouldn't resemble Yamato. The Musai was originally reversed, or rather upside-down, but it ended up like this for directorial reasons.

With something like Gundam, which isn't just a robot show but has a lot of serious humanistic content, I think the role of a mechanics designer is simply to provide seasoning to help depict the protagonist's way of life. So if you foreground the mecha too much, you'll lose the humanity of the characters. In the case of Gundam, I believe we struck a very good balance.

Seasoning is terribly important even when it doesn't come to the surface. And the background art that built the Gundam world is also important, even though it seldom comes to the forefront.

Looking back on it now, Gundam is surely SF, but I don't think it needs too much consciousness of SF. From the standpoint of designing mechanics, if you just take something that exists today and give it a slightly sharper form, it'll look science-fictional. Even with an antique carriage, for example, simply keeping the mechanism as is and replacing the wheels with boosters (rocket engines) will make it look like SF. But it's probably harder creating the world behind that.

Personally, I'm satisfied when the things I designed are depicted well, and in that respect the animators drew them even better than my own designs (and with a sense of weight as well). So as a mechanics designer, I have nothing to complain about. If there'd been time, there were some things I'd have liked to improve or revise a little. But under the circumstances, I think it would be self-indulgent for me not to be satisfied with the series as it is.

As a work, though, Gundam is a little too difficult. It's really hard to remember all the proper nouns. I'm a Gundam fan myself, but I think it would have been great if it could have been watched by slightly younger kids.

Since I entered this industry with Gatchaman, that's what left the biggest impression on me, but Gundam is surely in second place. It's a very memorable work for me. Gatchaman was pretty intense for its time, but in terms of aesthetics, I prefer Gundam. Ideally, after I do a harder work, I'd like to do a few gag shows like Daitarn in between, and restore my spirits before I do another hard show again. Anyway, Gundam is definitely a work I'd like to tackle again.

I've known Mr. Tomino for four or five years, since I was at Tatsunoko Pro. He was working as a storyboard artist and an episode director, but even back then, Mr. Tomino's storyboards were really unique. I had the impression of someone who was always restlessly scribbling.

We've been working together since Daitarn, and first and foremost he's a tough person. I can't match him when it comes to vitality. Even when he was so busy, he was still writing novels. That vitality is something to learn from. Anyway, he's been doing freelance work longer than me, so he gives me lots of advice.

If I had no choice, I might board the White Base or the Gundam, but I don't think I'd want to do it of my own accord. When I was in middle school, there were war movies like Ah, Etajima and Ah, Special Attack Unit. I really loved them at the time, so I thought about joining the Self-Defense Forces. And I had a relative who was into radio, so at one point I also thought about doing that...

In the end, though, it's better to look at space from afar.

I learned by watching my seniors, so of course I think it's important to do a lot of work. The unique thing about anime mecha is that you're destined to steadily get rid of as many lines as possible. In that situation, you're also assuming it'll be made into a three-dimensional object, and you can't give directions to the sponsors and manufacturers unless you can draw it with an understanding of its structure.

And it's not enough just to have descriptive abilities. When the mecha transforms and combines, there'll be parts you can't explain with drawings alone, but those points become obvious at a glance if you can build a three-dimensional model. So at the stage where you've figured out the structural aspects and you're wondering if you have the ability to depict them, it's probably important to have a mastery of model-making techniques.

Personally, I love to build things, and I still have more fun building things than drawing pictures.

Born on December 26, 1947. It seems he's loved building things ever since childhood. When he was in primary school, he made dolls with moving limbs out of bamboo, and he still remembers trying out various ways to make them move. Perhaps this became the foundation for coming up with mecha transformations and combinations.

He enrolled in the graphics department at Tokyo Zokei University. At the time, his interest in mechanical things hadn't yet begun to manifest, and the following year he transferred to the textile department. After graduating as a textiles major, he worked at the menswear company "Onward" and the baby clothes maker "Otogi no Kuni" before starting this job by sheer chance.

In 1972, he joined the art department at Tatsunoko Pro after he happened to see a newspaper advertisement and thought it sounded interesting. Here he had a fortunate encounter with his boss Mr. Mitsuki Nakamura. Though Mr. Okawara originally joined the department that made background art, Mr. Nakamura was also responsible for mecha at the time. This was also the point at which Gatchaman was starting, and so Mr. Okawara began doing mechanics design work.

Though he happened to end up doing mechanics design work, Mr. Okawara says he's not that obsessive about it, and he doesn't have a particular love for it. At first, he thought this work would disappear when Gatchaman ended. It's a specialized field, and it seems nobody around him had any idea this would be a long-running job. Mr. Okawara has kept on working as a mechanics designer because he continued on this path... It seems that's his honest feeling.

Even more than the grounding in ideas and sensibility that enables him to come up with new structures, new functions, and new forms one after another, the meticulous handiwork and effort involved in creating things, and above all his warm feelings towards the things he creates, are the great strengths that now sustain Mr. Okawara.

(1) Literally this could be interpreted as "there were no Zeon mobile suits," but it's possible Okawara just means the sponsor didn't request any.

What in the world is SF research, anyway? If you ask me, all I can say is that a storyteller is lying as if they'd really seen it. And the bigger the lie, the better. With a work like this, little lies will usually be crushed into invisibility, and when they're foregrounded it only makes their hollowness more obvious. Well, it's the same principle as a con artist, right?

That said, since a fictional world requires a plausible construction, it can't just be a pack of lies. You need some kind of foundation as well.

Let's take the Minovsky particle as an example. Without this, the close combat between mobile suits that takes place in Gundam would be a complete pipe dream. That's clear when you look at the state of electronic warfare as represented by present-day aircraft and naval vessels. In short, the current situation is turning into long-range warfare based on radio waves and long-distance weapons such as radar and missiles—with beam weapons now appearing, too—as well as ECM (electronic countermeasures) and ECCM (counter-ECM weapons). It's no longer an era where we can rely purely on human eyes, especially not in outer space. In an environment where nothing matters but detection capabilities, effective range, and destructive power, mobile suits with only short-distance combat capabilities would be laughable.

What to do, then? Of course, modern ECM technology will advance even further. But ECM and ECCM are just keeping pace with each other. Can't we come up with something with a wider scope, and which can't be so easily countered? The result was a fantastical electronic jamming material which we named the Minovsky particle.

The inspiration for the Minovsky particle came from somewhere surprisingly close at hand—the ionosphere. This is formed when molecules in the upper layers of the atmosphere are ionized by ultraviolet rays from the Sun. In broad terms, this is made up of two layers which extend from an altitude of about 100 to 400 kilometers. As we all know, radio waves with long wavelengths are reflected, and in some cases absorbed, by this ionosphere. The theory of the Minovsky particle was extrapolated from this concept, so that it can be used strategically and tactically.

The Minovsky particle is introduced as a previously undiscovered elementary particle. It has virtually zero rest mass, and the ordinary particle has a negative charge, while the antiparticle has a positive one. Since they have almost no mass, they normally pass through almost any kind of matter. When Minovsky particles are generated, they spread out at near-light speed, and the positive and negative particles align into a regularly spaced cubic lattice due to a force known as a T-force (transformation interaction). The electromagnetic wave effects produced by this cubic lattice interfere with the transmission of radio waves with longer wavelengths than ultra-microwaves. Thus infrared and laser sensors, and visual observation within the visible spectrum, are the only remaining means of detection.

Putting it simply, this means radar and radio communications don't work when you're even slightly separated. Of course, there's less interference at close range, so this doesn't mean they can't be used at all. So radio is still used in the show, but depending on the distance, there's noise in the voice and video signal. Lasers are used for long-distance communication, and infrared sensors are widely employed. (Incidentally, the Minovsky particle's name comes from the fact that Chief Director Tomino likes it.) (1)

Left: Long-range laser communications (tens of thousands of km). Image and sound are very clear.

Center: Short-range radio communications (a few km). No particular degradation of image and sound.

Right: Medium-range radio communications (10~20 km). Video sometimes distorted, sound interference.

The Minovsky particle is the product of complete fantasy, but it's one of the only examples of this in Gundam. This may come as a surprise to some people, but in the Gundam world's depiction of the near future, there are many things that seem to be an extension of reality. The most dramatic example is the space colony, as represented by the appearance of Side 7, where the story begins.

The space colony was actually a space development project jointly researched by NASA (America's National Aeronautics and Space Administration) and Stanford University. Most of the space colonies that appear in Gundam are based on the largest class from this project, known as the Island 3. Well, you can read more about this type of space colony elsewhere, and and it's even been featured on NHK Educational TV, so that's all I'll say about it here. If you'd like to know more, please see books like the following.

The space colonies of Side 3, however, are a little different. These have no windows for illumination. Thus, they can employ the entire inner surface of the cylinder, which makes them stronger as well as making it relatively easy to counter space debris and harmful radiation. On the other hand, they lose a lot of solar energy (sunlight) since they can't use it directly. This is because the solar energy is first converted to electricity by power satellites, and must then be transmitted to the colony to light its sunlamps. These power satellites, incidentally, are also an extension of a present-day plan. According to this plan, these would be huge power generators more than 10 kilometers on a side.

Their strength and shielding, and the installation of power satellites on the outside, are important aspects of Side 3's space colonies. This means that with only minor modifications, a Side 3 space colony can be turned into a Solar Ray, a giant laser cannon 6 kilometers in diameter, with no need for any new construction.

There's also the Federation Forces' Solar System, which is often confused with the Solar Ray. (This term originally meant the solar system made up of the sun and its planets, but it seems that recently it's also been used for solar-powered domestic water heaters.) Here, countless mirrors are arrayed in outer space and then controlled to focus sunlight on a single point, destroying the enemy with thousands of degrees of heat. In a sense, it's like a giant version of an ordinary concave mirror, no different from present-day solar power stations that use reflectors to focus sunlight and generate electricity. The concept can be traced all the way back to antiquity, when Archimedes was said to have used such mirrors to burn ships.

The mega particle cannon isn't some completely ridiculous death ray, either. According to reports published in America, it's been confirmed that the Soviet Union is developing beam weapons. Naturally, we can assume America is researching them as well. These come in various forms, from lasers to crude devices that directly employ the energy of a nuclear explosion as a beam weapon. The mega particle cannons in Gundam are a type of beam weapon known as a charged particle cannon.

A charged particle cannon resembles a cyclotron (particle accelerator). A cyclotron takes protons or deuterons, accelerates them to high speeds with a magnetic field that alternates between positive and negative charge, and then fires them. These accelerated protons and alpha particles serve as bullets to destroy atoms and examine their structure. The charged particle cannon uses exactly the same principle, accelerating and firing heavy metals and other kinds of particles. However much they're accelerated, though, they're far slower than the light speed of lasers. Moreover, their light rays can be seen even in outer space (a vacuum).

The shortcoming of this kind of beam cannon is that its power is greatly reduced in the atmosphere. For example, though the electron-beam gun used in the cathode-ray tube of a TV set has a very different purpose, its structure is very similar to that of a charged particle cannon. The only difference is that it shoots electrons and that their energy is vastly lower. The interior of a cathode-ray tube is almost a vacuum, and it fires an electron beam at a fluorescent screen tens of centimeters away. But what would happen if this electron-beam gun were fired in the atmosphere? The electron beam it emits could only travel a few centimeters. Likewise for a charged particle beam in the atmosphere, let alone in clouds or underwater. Having read this far, I think you'll understand why the White Base flies into a storm when it's being pursued by the Zanzibar and its fleet on Earth.

And finally, there's the mobile suit. Of course, the basic idea comes from Robert A. Heinlein's Starship Troopers (Hayakawa Publishing Corp.). The powered suits used by the mobile infantry in this story could be described as all-purpose personal tanks, which dramatically amplify the power of the person wearing them, but operate so delicately that they can grasp a raw egg without crushing it. The powered suit is also equipped with compact sensors, various firearms, and three jets, turning a flesh-and-blood person into a superhuman.

Of course, since there's nothing like the Minovsky particle in Starship Troopers, their range of activity is limited to the ground. Perhaps we could say that mobile suits like the Gundam are the result of first extending their area of operation into space, and then enlarging and diversifying their body shapes.

Writing it out like this, it might seem that powered suits and mobile suits are figments of the imagination like the Minovsky particle, but that's not necessarily the case. In reality, there are already multiplier devices that can be attached to the human body to give it power rivaling that of a forklift, and artificial arms and legs that amplify nerve impulses so that they can move just like human ones.

In this way, the world takes on a shape of its own through the accumulation of setting. Though this setting exists to drive the story, it can sometimes become a constraint on the work itself, inhibiting the work's potential. And since anime is the collective effort of many people, there can also be misunderstandings and miscommunications about the setting. Gundam is no exception. That's why it ended up that you can block a solid heat hawk with a beam saber.

Still, the fact that there are so many people pointing out where there are mistakes and where there aren't, and what about this and what about that, means we need to pay attention to these things. In other words, this is evidence that it's not a work without value.

Cooperation: Ah Nandason, Shoji Kawamori

(1) In other words, Minovsky = "Mino" + "suki" (likes). This is Matsuzaki's usual explanation for the name.

I forget which anime magazine it was, but in their review of Gundam, they said it felt like neorealism. "Hmm," I thought. Their observation wasn't unfounded, because that was a tendency I myself had sensed in the creator Mr. Tomino. I won't know whether or not he'd deny it unless I ask him, but I think he's at least a little influenced by neorealism.

I'm influenced by it too. It was seeing De Sica's Bicycle Thieves, which is considered a masterpiece of neorealism, that actually made me want to write scripts. Today's youngsters may not know this, but all the directors of the movies I later enjoyed, such as Godard and Antonioni who defined a generation, were people influenced by neorealism.

I think that for myself, and Mr. Tomino as well, that color probably came out in our works without us being conscious of it. So on that point, I had to say "Hmm" and accept it.

Speaking of neorealism, I think "A Female Spy on Board" is an episode where that color is relatively obvious. There's a scene where, amid the destruction of war, Miharu goes on her bicycle to meet with a fellow spy. This was Mr. Tomino's idea, but it's a scene that reminded me of old "Italian realist" (neorealist) movies. This is one of my favorite episodes, alongside "Reunion With Mother." I don't know whether I could write something like it again, but this episode let me do some things I'd always wanted to try at least once.

One was a situation where someone sells out their friends. Previously, I couldn't recall ever seeing a situation in TV anime where a regular cast member casually betrays their friends. At most, they might have had a guest character do it.

You could say Miharu is the reason Shiden decides to sell out his friends. She's someone whose first priority is making a living. Her approach to life is that, first and foremost, you have to eat. As a realist, Shiden sympathizes with her when he realizes this.

As I imagine it, in Shiden's life before he boarded the White Base, he was a youth who'd been shown nothing but lies. When they go about in a society that values lies and falsehoods, people become alienated. (1) Miharu is the first person Shiden has ever met who feels "genuine." This isn't a matter of likes and dislikes, or of good and evil. You could say he felt an undeniable sense of "human presence." Shiden sold out his friends because he felt this sense of reality. Even though he did hesitate...

Though Shiden is a bit of a coward, I think he's also unusually sensitive. Miharu feels the same way. Even if she thinks Shiden is a coward, she doesn't believe he's a weak person. Rather, when Shiden betrays his friends, I think she may have seen his strength.

As for Miharu, money is her number one concern, but she actually hates money more than anything. What I'm saying may sound strange, but that contrast makes me feel affection for her.

There's one other thing I wanted to do in this episode. They're just minor roles, but it's the handling of Miharu's little brother and sister.

In addition to their commonly described "angelic" side, I think children also have a ruthless aspect. But until I wrote this, it seemed like the children who appeared in dramas were mostly just treated as tools to tell sob stories, or to draw sympathy. That tendency was especially strong in TV period dramas. In short, I was dissatisfied that they were treated as little tools rather than as human beings. Things have changed since the days of Lone Wolf and Cub, but this still seems very common in Japanese dramas.

Getting back to the story, Miharu's younger siblings have a vague sense of what kind of job their big sister is doing. They certainly don't think it's a good one. That's why they're momentarily surprised when Shiden (a stranger) visits their home, and it seems like he's actively supporting their sister's work.

The previous depiction of children would have had them saying "Big sister, you shouldn't do this kind of job!" But in this work, I think I was able to show a different aspect of childhood. I'm grateful to Mr. Tomino that he let me write about and express this idea.

Since I've brought up Bicycle Thieves, here's an unforgettable story that has absolutely nothing to do with the movie. This was seven or eight years ago. I was out drinking with a junior colleague, who's now working as a director, and we got to talking about movies. I told him that watching Bicycle Thieves made me want to become a scriptwriter, but because he was young, he'd never heard of the movie. Of course, it's not like I'd seen it in its first release, either.

When this junior saw me a few days later, he immediately said "It's totally different from how you described it." I replied "What?" As we discussed it, we weren't on the same page at all. After a while, he asked me "A bicycle?" and I said "That's right, the father steals a bicycle." With that, he fell silent.

I later learned that this diligent student had gone to a bookstore and bought a book. It seems he wanted to learn about the movie that had inspired me, but the book he bought was called Car Thieves rather than bicycle ones. (2)

(1) Here, Hoshiyama uses the term "shirake" (白らけ), which is associated with Japan's apathetic, politically disengaged postwar generation.

(2) It's possible this book was William Faulkner's 1962 novel The Reivers, which was released in Japan the following year as Car Thieves.

Gundam was difficult. Perhaps it's because I started in the middle, but I didn't know how it had previously been going, or how it would go from now on. And then Amuro became a Newtype... That foreshadowing was a little hard to understand.

And after that, I did a lot of killing. First Ryu dies, and then Matilda, Hamon, and Miharu. (1) They were good people who died well. Miharu's death wasn't so good, though. Personally, I was dissatisfied with how that came out.

On the other hand, I really liked the final episode. That was all due to Mr. Yamazaki's abilities, though.

A thief stole some of the background art, so the production assistant Mr. Kusakari had to give up his New Year holidays to paint three or so replacement backgrounds.

As for the ending of the final episode, I can't say much because I never read the script, but all I can tell you is that it changed during the production process. The original plan was that we'd see a panoramic view of A Baoa Qu, and Amuro and the others would just be dazedly watching it, but that was pretty meaningless. The animators raised questions about it during a meeting, and they discussed various ideas with Mr. Tomino. He asked them to give him an hour or so, and he thought about it as hard as he could, ultimately deciding to show what had become of the Core Fighter.

Doing it that way was surely the right solution. We'd gone to the trouble of putting in an explosion, but there was no reason to just blankly stare at it, so we inserted the Core Fighter. It was a tool for war, and by showing onscreen what had happened to it, I think we were able to indicate whether or not the war was over. The Core Fighter disappears, so in short, the tools of war have gone away. Well, we don't know what's going to happen next, but I guess that's something for the people watching it on TV to think about.

You can play all kinds of games when you're doing the animation, but you can't play around with the episode direction on a serious work. Even if I'd wanted to, that wasn't possible for me. It was an exhausting work, but I'm glad I was able to do something of a kind I'd never done before. If there was something I didn't understand, I could ask and they'd explain it to me, and in that respect I learned a lot.

(1) Episode 21 of Mobile Suit Gundam, in which Ryu and Hamon die, is officially credited to episode director Susumu Gyoda. Sekita is credited with episodes 24 and 28, where Matilda and Miharu die. He also directed episodes 32 and 36, in which Dren, Dozle, and Sleggar exit.

Mr. Iizuka is someone who has been a huge help to all magazine editors, including those of the Complete Works. No-one but Mr. Iizuka could organize all of Gundam's setting materials, bank cels, and so forth.

—What? I'm being featured in a behind-the-scenes interview? Aren't there a lot of other staff? What about Sacchan (Mrs. Sanae Takegawa), who's in charge of the bank? (1) Mr. Tomino said he'd really like her to be included. Even if she says "I've already appeared, so they shouldn't put me in this time," the other staff must have said the same thing. But I guess there's no choice, so let's talk.

I always end up with the complicated stuff...

The Sunrise planning office.

You're asking what I do? I'm the odd-job guy they call the planning office desk chief. They make me do anything and everything. Ha ha, for one thing, it's the planning office's job to contact sponsors, and since mecha names is particular are often used in merchandising, they're initially proposed by the planning office. After that, they're submitted via Mr. Tomino on the production site.

With "Gundam," it was Mr. Yamaura who took the initiative. But of course it was ultimately Mr. Tomino who decided, saying that was good. "Guncannon" and "Guntank" were decided by myself and Mr. Tomino. The series director's intentions are particularly crucial in a work like Gundam, so the original ideas come from Mr. Tomino and then we just select from them.

As for the issue of size, when we were wondering how large they should be, we had to make them bigger because of the sponsor. But we didn't want to make them too big, so we ended up making them 18 meters, because that's ten times the height of a well-built adult male. The Tank and Cannon were adjusted to be proportional to that... With the internal diagrams, in deciding the names of all the parts such as engines and radar, we had to go through Mr. Tomino. Then we made them clear and released them. (2)

Gundam was heavily covered in the magazines, wasn't it? We took the sales department's intentions into account, and once I fully understood what they wanted to show, I'd pass along the materials. So if a certain magazine said they wanted setting sheets for the White Base, it was my job to get them copies. I do all the work aside from creating the film, so while I'm not the Takeo General Company, it feels like I'm Sunrise's jack of all trades. (3)

Agh, don't take photos! You'll suck out my life... I guess there's no choice. Just one, then.

This mecha illustration? Well, let's just say it's a job for a certain magazine... or something.

Mr. Iizuka at work.

Nippon Sunrise is a company that can do anything related to animation. So we worked with Mr. Tomino on things like title design, too. And Gundam's color coordination? Naturally we did that as well. We considered the intentions of the production site, as well as our relationship with the sponsor, and came up with a compromise. The planning office gave it a lot of thought and decided on tentative colors, then incorporated the ideas of the sponsor's designers to arrive at the broadcast versions.

We helped out a lot with the Complete Works, too. But that's only natural since they're Sunrise's own books. During Gundam, Hiroshi here (Ms. Hiroshi Kazama of the planning office) was working on 009, but since she knows so much about Gundam, recently I've been pushing more and more Gundam work on her. (4) The character sheets in the color pages were her work... Come here for a second, Hiroshi. They'll take your picture for free. Hey, press the shutter, ha ha.

Working alongside Ms. Hiroshi Kazama.

We're talking about behind the scenes, but since animation is collaborative work, isn't everyone behind the scenes? With Gundam and Ideon, not only the staff but the whole company is involved, so Sunrise is a rewarding place to work. That's a nice sentiment, isn't it? It seems like a fitting way to end the Complete Works. Anything to add, Hiroshi?

—As far as memorable anecdotes, one time when my schedule was really chaotic, I went to Studio 1 in the middle of the night, and Mr. Tomino was there drawing storyboards in his long undershorts. He looked at me and said "You saw me?" and I replied "Yes, I did." "I've been spotted," he said dejectedly, and went back to work.

—Ha ha, we'll leave the rest to the editors. Please put it together for the Complete Works.

—Since we were talking to Mr. Iizuka, who played a huge role in the creation of the Gundam Complete Works, just for variety we wanted to record his unedited remarks. Unlike traditional anime, a lot of setting documents have been circulated for Gundam, and that's surely due to the meticulousness of Mr. Iizuka's materials management. There could be no person more fitting to conclude the Complete Works.

(End)

(1) Production secretary Sanae Takegawa was featured in the staff comments in Complete Works 1.

(2) These internal cutaway diagrams, and other publicly released setting, feature Iizuka's handwritten text.

(3) The Takeo General Company is the business run by the hero in The Unchallengeable Trider G7.

(4) Kazama's real name is Yoshie Kawahara. She was actually working on The☆Ultraman during the broadcast of Mobile Suit Gundam.

Mobile Suit Gundam is copyright © Sotsu • Sunrise. Everything else on this site, and all original text and pictures, are copyright Mark Simmons.